The Ballad of Punk-Rock Superman

(or Why James Gunn's Superman Is The Best Superman Movie, fight me)

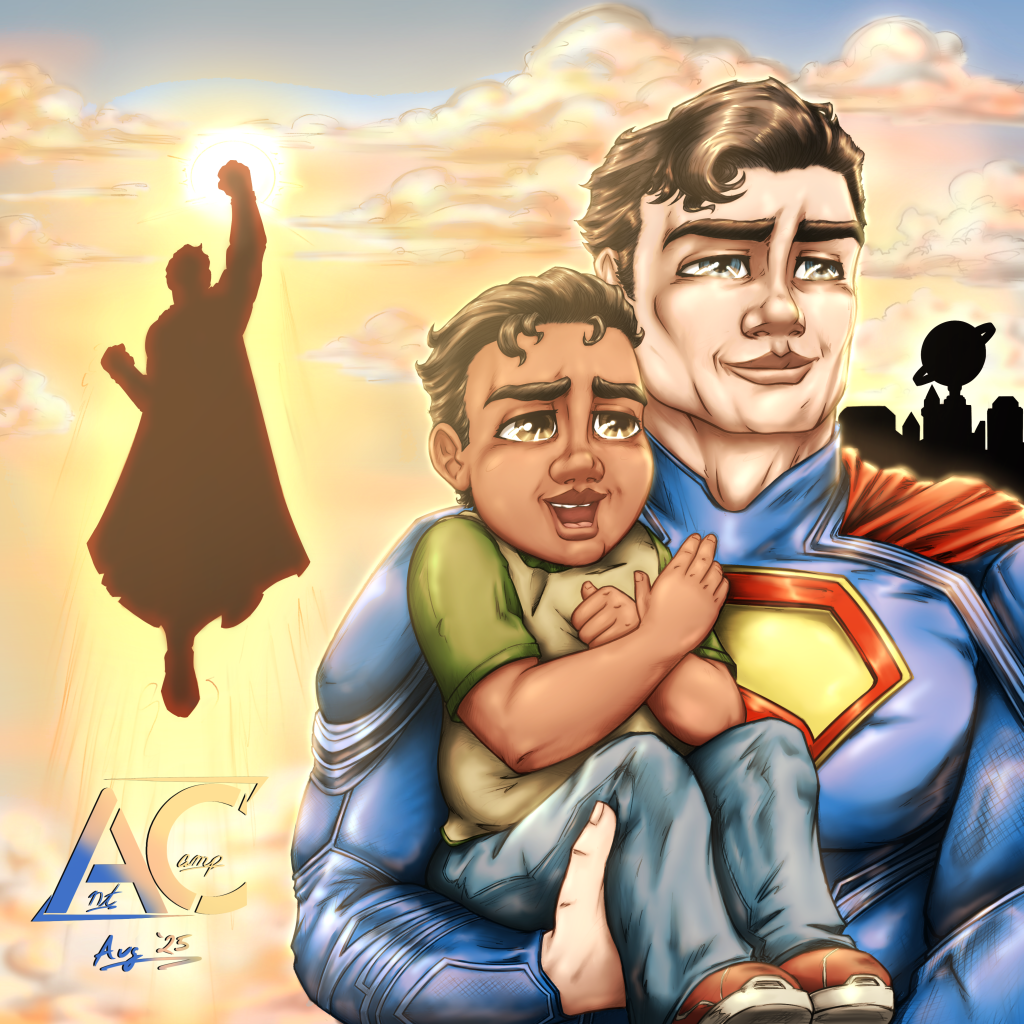

By Anthony Michael Campney - September 2025

“Maybe kindness is the new punk rock,” said Superman.

You’re likely a little sick of seeing that line smeared all over social media. If so, fair enough, I invite you to leave now because this essay only gets worse for you.

In the spirit of punk-rock-kindness, I give you dear readers fair warning: profanity, spoilers for most Superman films ever made, and a lot of mushy so-called-liberal-agenda politics abound in this essay. Again, if such things get your red wrestler trunks in a twist, this essay will likely only piss you off.

Or, on the other hand, maybe you’re exactly the kind of person that should hear what I have to say; I leave it to you.

Something has been wrong with mainstream public perception of Superman for quite some time, and despite the griping of many to “keep politics out of my entertainment!” there is no denying that the growing vitriol over how Superman has been perceived and even utilized in media over the last few decades has paralleled real world history and politics in oftentimes eerie ways. Look no further than the year 2000 election of Lex Luthor to the office of United States President in DC Comics lore; this storyline was hailed as a strange parallel then by the leftwing detractors of the Bush administration; in the wild world of August 2025, the entire President Luthor arc is considered downright prophetic of the Reign of Trump. But the deepest debates over Clark Kent’s meta-handling are held around what exactly Superman does and does not represent and, from that standpoint, how he would and would not react to the various circumstances at hand in any given historical moment. It is from such a place that talking heads have raged over the swapping of “and The American Way” for “and A Better Tomorrow.” It’s where self-proclaimed acolytes of Zack Snyder have carried out digital outrage in the name of “peak Superman,” and Dean Cain – the actor who played Superman in the 90’s Lois and Clark television series – feels motivated to tear the latest film entry apart for making Superman “woke.”

There are myriad other articles – written by people far smarter and more in touch with political machinery than I am – that dig into the politics of the moment and how the current social discourse has brought us here, to which the political debate over Superman’s representation is merely a sidebar/side-effect. But as someone who has been a deep-seated Superman fan since he was seven years old (that’s over thirty years of reading Superman comics and ruminating on his various themes and ideals), I can speak pretty confidently on what Superman is and is not about, regardless of any individual’s specific political leanings. It has always struck me funny that, whenever I have asked the casual movie goer (aka not someone deeply invested in the source comic book material) what their view of Superman is, whether or not they care much for the character their summation of Superman generally runs the same: a god-like being who serves as a modern day savior for the people of Earth and overall represents the best tenets of decency, hope, and helping your fellow man. It’s no wonder then that, up until James Gunn’s DC Studios production this year, every Superman film has built its story, themes, and overall message on this broad view. From Christopher Reeve through Brandon Routh and on to Henry Cavill, each Superman film from 1978 on has collectively gasped in wonder at the sight of a man that can fly and represents pure, pristine (and honestly kinda puritanical) capital-H-but-somehow-represented-by-an-S Hope. To some extent or another, each of these films was a messiah tale.

All of this leads me directly to a statement that I know will piss many off and baffle still more and I still choose to stand by it:

James Gunn’s “Superman” is the best Superman movie made so far.

Yes, better than Man of Steel.

Yes, better than Superman The Movie in 1978.

Is David Corenswet’s performance better than Christopher Reeve’s? Eh…that’s a different discussion for a separate article as it’s beside the point I’m making here, though I will be making a point later about what contributes to defining such qualities of performance.

I’ll get into the details of where my opinion comes from exactly and how I came to this conclusion while picking apart the movie itself, of course. But it all boils down to this for me: Superman 2025 is the best of the Super-films because it is the first and thus far only movie to put the majority of its focus on Superman-the-Man, not Superman-the-idol-for-the-rest-of-the-cast-to-react-to.

Years Of Looking Up In The Sky

Because this is not going to be an unbiased high-level review of the movie’s isolated merits, I feel it pertinent to provide at least a general sense of where I’m coming from in my particular Superman love and the perspective I had on the character going into watching the film for the first time. As previously stated, I was seven years old when I first became an official, die-hard Superman fan, and as some people reading this have heard me describe multiple times in the past already, it all started (quite ironically) with The Death of Superman (Superman vol. 2 issue 75, 1992). Up to that point, I enjoyed Superman in the way any kid in America – particularly boys, as at that time we were the ones predominantly marketed to with superhero media – generally liked superheroes; if anything, my attention was more on Batman and the X-Men given the movies of the former and the animated series of both that were so popular in the early 90’s. I had a high-level understanding of Superman’s story, origin, powers and position as the first official superhero in comics. I had caught some clips of the Christopher Reeve films here and there on televised reruns, even watched a handful of episodes of George Reeves’ Adventures of Superman. I had seen bits of the Superboy television series that seemed to randomly vanish without a trace (my knowledge of the effects of the incoming Lois & Clark show sorely lacking), and I was entertained by the classic and somehow still awesome looking Fleischer cartoon shorts. Super Friends and the like were all but off the air. My exposure to Superman hadn’t been all that wide, I hadn’t laid hands on an actual Superman comic yet, and I was growing more and more aware of a general sense that Superman simultaneously exemplified all the great attributes of heroism and basic human decency on the one hand, and on the other was regarded as something of a boring and childish character. Older kids and teenagers that I had discussions with about Superman cited enjoying Super Friends as little kids – aka before they “grew up” – and even being wowed by the sight of Christopher Reeve flying across cinema screens during some of their first movie-going experiences, but also expressed how that wonder wore off as they got older; I didn’t have the language or understanding at the time to properly translate what I was hearing, but retrospect told me Superman was considered a pretty neat character to watch and want to live up to for kiddos of a certain stage in life…until innocence began to waver and the “real world” crept in, at which point Superman seemed pretty silly and irrelevant in the face of more “real” characters like Batman and The Punisher. Even superpowered and hyper-realized superheroes like Spider-Man and the X-Men were viewed as preferrable to Superman given they faced more realistic stakes than an invulnerable sun god and traded in dealing with superpower-filtered versions of real-world issues like bigotry and living paycheck-to-paycheck.

Chief among the complaints around Superman’s boring and outdated nature was his lack of vulnerability: unless kryptonite was involved or some other random retcon of his great powers, there was never a way to hurt the guy and you could only threaten his emotions with tied-up Lois Lanes and Jimmy Olsens so often before it got tired. This was the view of Superman most promulgated back then in mainstream media, and it was the view of him most reinforced in kids of my generation going into the 90’s.

I’ve written a whole other essay (hence I’ll keep this go ‘round brief) about the morning my second-grade teacher, taking note of my love of drawing and superheroes in general, allowed me to borrow time in her classroom to read her son’s plastic-wrapped copy of Superman #75, the issue where he fights the brutal alien monster Doomsday to a standstill, defeating the creature but dying in the process. That was my first encounter with not only the idea that Superman could even be harmed in such a violent and combative fashion, but also the fact that a Superman story could be told with such visceral high drama. Far from saving cats out of trees and greeting citizens with a smile, this Superman was engaged in hardcore combat against a force of raw violence arguably more powerful than himself. This was the beginning of my understanding that Superman brought with him far more engaging and interesting stories told and yet to tell than I ever would have guessed off of the mainstream perspective that I had grown up on. And on that note, it wasn’t long before I came to understand that I had stumbled onto the exact problem right there: the source material for Superman stories, his comic books, had long ago grown up and evolved into substantial, thematically rich literature – brought to life in gorgeous and modern artwork – far beyond the infantile and boring image most non-comic-book-reading people had of the character. It’s no wonder that a few months later, when the Lois & Clark television series premiered – replete with sexy marketing ads of the lead actors and featuring bold “modern” takes on the title characters – general audiences were taken aback by the “fresh” take. In reality, Dean Cain and Teri Hatcher’s takes on their respective characters were extremely close to the versions of Clark Kent and Lois Lane that had been running Superman’s comics since the big DC corporate shake-up in the Crisis days of ’85 (the year I was born, I said with a chuckle). Ever since John Byrne revitalized and streamlined Clark and his adventures in his Man of Steel miniseries, comic readers had been enjoying a much more forthright and dare I say assertive take on Superman. He hadn’t lost the boy scout sensibilities or the compassion and warmth of Christopher Reeve’s pitch perfect performance at all, but now Superman was drawn and written to be someone prepared to throw fists against opponents who could not only take such mountain-shattering hits but also dish them right back out. As I dug through back issues of the comics leading up to the Doomsday battle, I came to understand that Clark now had far more physical vulnerabilities – magic and red solar energy, to name a few – but even more than that, the writers of the day were actually treading new ground and digging into interesting challenges to Clark’s character. He had a slight sense of grit to him now, a determination to stop those who would harm others and defend the defenseless in a modern-reflecting world that not only actively and wantonly sought to take advantage of average citizens, but do so with a sense of cynicism and apathy that Clark simply could not abide. The more real and grounded dark forces in the modern world only called out the need for the kind of heroism Clark provided all the more.

In case you haven’t been paying attention: the comics were good. They were modern, action-packed, full of theme and pathos. They rooted Clark’s character development in how a vastly superpowered man who is genuinely as good as he is powerful reacts to the kinds of moral threats the modern world provides, realized in equal measure by both superpowered villains as metaphor and criminals reflecting very real-life villains, such as the Trump-inspired revamping of Lex Luthor (a decision made in the mid-80’s, long before he was ever president). Engaging Clark with such modern sensibilities naturally crafted a storytelling environment that wound up doing much more interesting things with the character and his fictional world than Christopher Reeve’s films ever touched.

The Never-Ending Battle For Character

Lots has happened with the Man of Steel on film to lead us to this point, and it pays to have these evolution points in mind going into discussing the latest film.

Now, I realize I have been lightly shitting on Christopher Reeve’s films up to now, so let me make my opinion clear (as well as put credit where it’s definitely due): I don’t hate the original four films, far from it actually. They have a ton of merits, not least because they set the bar for core material respect in comic book films and gave us the almighty Legend of Christopher Reeve (no irony or sarcasm; God rest the man). Like most fans, I don’t choose of my own volition to rewatch Superman III or IV or even the poor Supergirl film very often because those films were horribly underserved from a writing standpoint alone. But respect is certainly commanded and deserved for the fact these were pretty much the only cinematic experiences for superhero fans for a good decade, and even 1989’s Batman from Tim Burton simply took the torch from the Superman films; we really didn’t see a proliferation of these properties at the box office until the early 2000’s when Marvel finally got its shit together.

The truth is: Superman The Movie (1978) and Superman II (1980) did a fantastic job of introducing mainstream audiences to a more grown-up yet still family-friendly take on the Last Son of Krypton. It was a version that simultaneously paid proper homage to the comic book, cartoon, and black-and-white George Reeves portrayals before it that everyone remembered while also shifting Clark into the then-modern times and making the character emotionally and physically believable (“You’ll Believe A Man Can Fly” was always meant to work on multiple levels). The production of the two films – famously shot back-to-back with Richard Donner running most of the show until differences with the executives cropped up near the end of Superman II’s production, prompting Richard Lester to replace him – was visually stunning and effective in grounding the first substantial attempt at Superman in cinematic live action. But personally, I think most will agree with me that the vast majority of what makes those two films land so well even today is Christopher Reeve’s performance in and of itself. A debate can be had another time about who played the character best out of the various film and television actors that have had the pleasure, but I’m of the mind that Reeve deserves a protected status as a legend all his own; there’s just no point comparing any other actor in the role to this man. His struggles and truly awesome humanitarian deeds outside of the film world are too tightly related back to his role as the Earth’s greatest fictional defender to give any other actor a fair comparison. However, it goes even further than that to a very specific point that relates directly to the 2025 film.

In my view, the very reason Christopher Reeve’s performance is remembered so well – and justifiably so – is because, honestly, the character wasn’t written that great in his films.

If you really isolate Clark Kent and/or Superman’s actual dialogue in the film – particularly in the latter 60% of the movie in which Reeve plays him as a grown man – his actual lines aren’t that good. There’s not a lot of pathos or drama or emotion or even comedy to his lines as written in the script. Some of his bumbling-Clark dialogue lands a chuckle, and his interaction with Marlon Brando’s holographic head in the Fortress of Solitude gives a rare insight into Superman’s emotional vulnerabilities, but as-written the interesting stuff stops there. Everything interesting about Clark/Superman that we remember from especially the first film really resonates far less from the script and much more from Reeve’s performance: his body language, the look in his eye, the tenor of his voice, the delivery of the lines he got. Everyone who has ever watched that film remembers the moment Reeve sold us all on the idea that yeah, maybe this guy actually could pull off being Superman without a mask/using nothing but glasses as a disguise. The scene in Lois’s apartment where he almost reveals himself…the way Reeve uses his Julliard training and experiences in the theater circuit to display two distinct personalities – down to posture, vocal octaves, mannerisms, where his eyes go – that’s the stuff that made his performance real and ever impactful, to the point John Byrne leaned hard on those specific choices to explain Clark’s performance decisions in the comic book reboot. A lesser actor (or one taking the role less seriously, anyway) never would have landed the character in the collective public consciousness the way Reeve did relying solely on the script.

Short version: the absolute lightning-in-a-bottle casting choice of Christopher Reeve saved Clark’s character quality in those early films. Without Christopher Reeve, I don’t think audiences actually would have believed a man could fly, at least not in that context. Because the reality is that, past a light cuss word or two and some jokey references to rape and murder, the script as it stood had lofty ideals executed in fairly cartoonish fashion, not far from the Super Friends-esque milquetoast boy-scout image mainstream audiences already had in their heads of the character. Everything interesting about Clark in these films came directly from what Reeves added to it, not from the writing. The script went far more out of its way developing the characters of Lois Lane, Lex Luthor, and God-help-me Clark’s bio-dad Jor-El; we spend more time lingering in the wake of Brando’s Shakespearean turn as his son’s Voice-of-God going into Clark’s Christ-themed heroic career in this movie than we ever do actually getting under Clark’s skin and feeling what he feels. Most of the movie is about how the supporting cast reacts to Superman, not how Clark deals with being who he is under that microscope. In this context, Reeves pretty much saves the whole project with his performance just by almost literally breathing life into an otherwise underdeveloped character.

And while the aforementioned Lois & Clark, then the Superman animated series of the 90’s, and later on the hit show Smallville made great strides in leaning harder and harder into the post-John Byrne ethos of a dramatic, interesting, thematically challenging Superman, all of them were subject to the shackles of television censorship, executive directives, and the general limitations of the times. Multiply these issues tenfold when it comes to what a big budget studio production is going to allow, and presenting the evolved, modern-yet-still-classic Superman comic book readers had grown accustomed to on film was a tall order.

Hence: Superman Returns.

Look, I get what Bryan Singer and company were shooting for in 2006, I really do. And the movie has a lot of really good components strewn throughout (Brandon Routh does a far better job with what he had to work with than anyone had any right to expect of a barely-known actor at the time, and that airplane-save sequence is a peak-live-action-Superman moment), but all good intentions toward the memory of the then-recently-deceased Christopher Reeve aside…no one asked for that. No one wanted to return so specifically to that version of Superman without any of the actors (save the digital ghost of Marlon Brando) that populated it, especially in a world where Marvel films had run the ball of what superhero movies could be and do far beyond what Supermans 1 – 4 had set the stage for.

Swing and a miss.

Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel came to the table next in 2013 with much more promise and/or potential (depending on your view): guided by the likes of Christopher Nolan and David Goyer, the masterminds of the highly successful Dark Knight trilogy of Batman films, Snyder himself had cut his teeth on at least visually faithful adaptations of Frank Miller’s 300 and Alan Moore/David Gibbons’ Watchmen. Add to that the trailers proved quickly that this film not only owed quite a bit to the likes of the Smallville show and more recent story developments in the ongoing comics, but as such this film would be shooting for a much more raw and grounded atmosphere with plenty of explosive action, really maximizing the ability of modern special effects to showcase the awe and impact of Clark’s powers. I have to say, I went into viewing this one with a lot of hope and excitement.

I can’t say it disappointed per se, but…

We’re here to primarily discuss the 2025 film, so I won’t spend a ton of time here. However, it’s pertinent to touch on because Man of Steel – just within the fact that it was the last standalone Superman film made prior to 2025’s Superman – is the film most commonly being compared to James Gunn’s film, followed loosely by Richard Donner’s 1978 original. A big part of that comparison is derived from the – love it or hate it – much more dour and melancholy atmosphere of MoS in comparison to the quite colorful and lively 2025 film. Die-hard lovers of Man of Steel and of Zack Snyder tend to view it as the only time a mainstream Superman story has been cool and entertaining because it finally got the character away from boring “greetings, citizen” black-and-white outlooks. Detractors view it as a complete and total abandonment of what makes the character work and the world he inhabits fun to visit. Personally, I think both sides get it wrong and its why I have a lot of love for Man of Steel while simultaneously finding myself unable to ignore its glaring flaws. MoS was a film with a very strict and particular edict: it was exploring what it would be like if Clark Kent, with the core basic elements of his character, supporting cast, and backstory in place, existed in the real world as we know it. Right from the outset, this is a premise that nearly guarantees losing a good chunk of the audience, both mainstream and longtime-comic-fans, because baked into that very premise is a necessity to abandon certain things that have, in many people’s minds, always defined Superman. I personally never had a problem with Clark killing Zod in the climax of Man of Steel. On top of the often-overlooked fact that both the comics (see The Supergirl Saga of 1988, beginning in Superman vol.2 #21) and the theatrical cut of Superman II in 1980 granted precedent to Clark doing such a thing (to that specific villain, no less), I also understood the thematic and internal-logic parameters within which Clark was being brought to that action: it was the final, point-of-no-return decision to choose present day humanity over the harmful remnants of his previous culture, combined with the fact that, in such a realistically realized world, no technology existed that could possibly confine Zod and keep him from destroying the planet with his bare hands. Given the rock-and-a-hard-place choice of only those two options – kill Zod or he’s going to keep right on killing innocents, no other possible option – Clark is not going to effectively kill innocents by proxy for the sake of maintaining an arbitrary no-kill rule against the villain for no other logical reason than to placate comic fans. The realism of the film’s set-up and premise necessitated that Clark make a choice he ordinarily wouldn’t have to in, say, a more cartoonish or comic book-adherent world, or at least one populated by other heroes and/or more advanced technology that could assist with such things. By default, this upset a lot of people, people given to grasping at straws on social media for other ways a “true Superman” would’ve handled it when the reality is we just don’t really like seeing Superman put to such realistic decisions. It was a poignant moment in the evolution of superhero cinema and superhero storytelling for checking just how far we as audiences really want to go on the realistic-superhero train. These characters exist in the kinds of realities they do in comics for a reason, and this point is writ large in the 2025 film.

Again, Man of Steel had its flaws: far beyond Zod’s execution, I was personally much more aggrieved of Clark watching Jonathan Kent be taken by a tornado in respect to Jonathan’s wish that Clark wait until he’s ready to reveal himself; as much as I respect where this was attempting to go thematically, it’s simply not a thing any version of Clark Kent would ever do. But I enjoyed and respected what the film was attempting to explore, and I genuinely felt the cast and crew pouring their blood, sweat and tears into the production. A true sequel (aka not the studio-chopped theatrical releases of Batman v Superman and Justice League) would have been interesting to see, not least because the film pretty much ended right when we were going to see the classic elements of Superman’s life and environment catch up with this gritty-and-realistic atmosphere Snyder had set up. Alas, both the film as it stood – and its anxious-to-set-up-a-shared-universe follow ups – opted to primarily rely on the same core problem that Reeve’s films and Superman Returns fell prey to: far too much focus on everyone else’s reactions to Superman’s existence, and not nearly enough exploration of Clark Kent the character, Clark Kent the Man. The script for MoS goes leaps and bounds beyond Superman The Movie and its follow-ups in actually giving Clark things to say and do beyond his superpowers; the dialogues he holds with his parents and Lois and even a priest (there’s that Christ theme again; just look over Clark’s shoulder in that scene) are much more rooted in a legitimate attempt to know Clark’s thoughts and feelings, but these are still pretty fleeting. Most of the film is run in service of the shock to the world of Superman’s existence, and less so what Superman is going through as a character. It tries hard to develop him and give him an arc, so we can call it progress, but it never quite sticks the landing. What Clark has learned and how he has grown by the end of the film is fairly muddy.

And this brings us full circle and right to home, folks. Because while other people’s reactions to Superman do help fuel the overarching plot of James Gunn’s Superman, the core focus of the film is Clark Kent, through-and-through, without question. The majority of the film is from Clark’s perspective. We are offered glimpses of – yup, I’m gonna say it – character flaws of Clark’s because he’s not actually a god or any other kind of perfect being. He actually has personal flaws that he must confront and attempt to resolve as the film plays out. And while I have not researched this so it’s possible I’m wrong, I’m pretty sure this movie has by far the most lines actually spoken by Superman in any of his films.

Oh, and “invulnerability” makes him boring?

Clark gives as good as he gets, but…he does get his ass whupped in this movie. A lot. Like, the film literally starts with him crashing into the ice outside his fortress with broken bones and a crafted-by-Mike-Tyson bloodied face. Almost as if it were, you know, intended to telegraph to the audience that we just might well and truly relate to this version of Superman on film.

Mild-Mannered Superman

If you’re reading this, you’ve likely seen the movie and heard the plot picked apart to death, so let’s just skip that part.

For the sake of being my own devil’s advocate: this movie is not perfect either. Leaning on Krypto – as adorable as he was and I can’t wait for more of him – got a bit distracting at times. The film is filled with side characters who received varying degrees of development due to said overstuffing, so it can be argued that some were unnecessary; my own daughter makes a pretty strong argument for the gross underdevelopment of the female characters in the film, which I do think there’s some truth to, at least outside of Lois. My biggest gripe is an ironic one: as much as I love how much this film got under Clark’s skin and put his thoughts, emotions, and actual character on parade, we spend literally one brief scene in the Daily Planet with glasses-wearing, suit-and-tie Clark Kent. You’d think we would have at least seen him at a DP office party during the end credits or something.

So yes, the film has flaws. Flaws are inevitable. Flaws are human, much like the Clark Kent, specifically the very human and realized version of Clark Kent we get in this film.

Every version of Superman on film – even Christopher Reeve’s – bled and showed vulnerability at some point, so the fact that James Gunn’s Superman gives us a bloodied and battered Superman is not novel on its own. The fact the film opens that way – after telling us in the narrative text that Superman just faced his first loss in battle three years into his heroic career – telegraphs a lot of information to the audience that grabs our attention. He’s just come up against something even he couldn’t beat, which, going right back to my experience reading his battle with Doomsday thirty years ago, begs all kinds of questions about how he’s going to have to change and evolve, even grow as a person in order to meet this challenge again. In the meantime, he’s had his ass handed to him right in front of the viewing public, which will have its own repercussions.

I’ve beat the drum of everyone-else’s-reactions-to-Superman quite a bit throughout this essay, so let me acknowledge that this film is not devoid of that either; rather it spends far less time on it and the attention it does give to it is quite different and much more nuanced. This movie isn’t interested in using Clark as a Christ parable or any other flavor of messiah. In fact, the movie makes the point that while many in the world view him as existing on such a level of godhood – whether as a heavenly savior or the kind of huckster devil that Nicholas Hoult’s awesomely seething Lex Luthor clearly takes him for – said godhood is a fallacy, a mirage that the masses have attributed to a person who, in reality, is simply a guy trying to get by in the world like everyone else; he just happens to have these crazy powers, with which he chooses to aid those around him.

That last point – the overpowered everyman doing his best – is a shorthand understanding of Superman’s character that comic book fans and even followers of the television media around Superman have understood for a long time. But as I’ve outlined, it’s something the movies have invariably kind of put out there, but inevitably overpowered with their messianic leanings. Up to this point, when films have been made about Superman, the knee-jerk urge in writing the character seems to be to give audiences – namely Americans, let’s not bullshit – a savior for our times, a modern-day God-Made-Flesh that hails from the American heartland and, even if we’re not using “…and the American Way” out loud, lives to espouse the values of the good ol’ USA. Because here in the real world, real figures like the US president or sports stars or everything down to police officers that we should be able to look up to and be inspired by just aren’t cutting it these days, at least in the present grand scheme. It’s true that characters like Superman were designed to serve as parable and/or even totemic stand-ins for real world heroes, but there is deep folly in taking this too literally. These myths can do a lot of good as symbols with which to inspire oneself, but taking them to the point of borderline worship or, conversely, accusing them of indoctrinating the masses toward harmful paths is several steps too far.

This is a subject that James Gunn’s Superman takes absolutely no prisoners on in a variety of manners, some screaming loud and some quiet and subtle. But the best flashpoint for this focus of false deity attribution versus messy-yet-aspirational truth is the now infamous Interview Scene.

Easily the most important scene in the movie as it both sets the stage for the film’s themes and foreshadows the growing up that Clark will have to do, the scene where Lois interviews “Superman” – aka Clark behaving in “character” as his high-flying alter ego – is the best superhero film scene since the late great Heath Ledger, in full Joker make-up, dressed down Christian Bale’s Batman in the police interrogation room in The Dark Knight. Rachel Brosnahan earns her stripes as Lois Lane here; for a long time I’ve maintained Teri Hatcher was the best live action Lois Lane, but personal childhood crush biases aside, I think I have to give it to Brosnahan now, especially after this scene. Brosnahan spends this scene not only showing – not just talking about – Lois’s journalistic skills and sharp mind, to say nothing of her dedication to objective truth. The union of writing and performance here goes a long way toward shoring up Lois’s convictions that while she can base valid opinions on the most likely common-sense scenarios at hand, there is a difference between informed opinion and actual facts, something she holds Clark to account for especially on account of him being a fellow journalist in his day job; put another way, she pretty much tells him that, as a journalist, he should know better than to take decisions on what he thinks he knows. This not only showcases Lois’s intelligence and proverbial teeth, but it is a far cry from basically every past portrayal of Lois. With the notable exception of Bitsie Tulloch on the CW’s Superman and Lois, every other live-action Lois, to some degree or another, showed up as an edgy, sensual, borderline-cutthroat professional until Superman showed up and we all had to watch her descend into some variation of willowy romantic tizzy. Brosnahan’s Lois is not wondering whether or not Clark can read her mind, she’s far more concerned with making sure he’s thinking through his own actions.

Which brings us to the other fantastic point about this scene, which is (one more time): flawed Superman! The third-person one-liner jokes aside, I was ecstatic to see a version of Clark that gets aggravated about having his less-than-PC decisions held against him. He just wants to have a fun night with his girlfriend after a rough day, maybe even get a little pity-pampering given the beating he took earlier, and instead he’s facing a very different and yet somehow more brutal beating: the woman he’s falling in love with is pointing out all sorts of holes in his logic when he was gut-sure he had done the right thing in stopping a genocide and threatening the dictator who ordered it. And I think most people are agreed that Lois’s argument doesn’t necessarily prove Clark wrong in doing those things, but the way he went about it and the outright callousness – dare I say arrogance – that he shows toward acknowledging any kind of authority from international governments is a low-key sign that he still has some learning curves to master on this path he’s chosen.

And speaking of choice: how about the reveal that – in Clark’s mind, anyway – he does what he does because his bio-parents wished him to be the Earth’s protector? Obviously the reveal of the whole harem thing with the rest of the message was a shocker and an interesting storytelling risk to take, but the payoff is far more interesting to me: Clark is put to outright deciding – or acknowledging that, deep down, he had already decided – to be a champion for goodness and helping the helpless because that’s who he is, and not because it’s expected of him by long dead parents he never knew who hailed from a failed and self-destructive culture. He chooses to be Superman. He chooses to be good. And by the end of the film, between what he’s been through in the movie and what he learns through his interactions with Lois and the Kents and other heroes around him, he chooses to do good in a manner far more respectful to the concerns of other people. And all the while, we’re not just told that Clark is a symbol of hope, we’re outright shown what he inspires in other people: fear in dictators; sickening envy in those (Lex) who think they enjoy real power with money and ingenuity until a truly wholesome person comes along; love from those whom he has given love; and true, selfless heroism from other heroes.

Once again, I need to give credit where it’s due: I do think most, if not all of these points were attempted by previous incarnations; it’s not like Donner, Snyder and the rest just ignored these points outright. But the human and inspirational aspects of Superman were given far less attention and paid mostly lip service in the name of pushing a much more Americhristian theme for the character, one that I’m not even sure all of these filmmakers were cognizant they were doing. Superman in 2025 deliberately chooses to eschew that easy road of Superman = New Christ for a version of the character that is more flawed, therefore more human, and therefore much more interesting. We see Clark lose his temper. We see him behave a little petulantly. We see him cry and agonize over the needless death of an innocent man. And in the face of all of the horror and physical assault and total disregard for his God-given rights as a person that Lex Luthor pours onto Clark from the very beginning of the film, Corenswet’s Superman still tries to reason with Lex in the end. He still attempts to inspire his most hateful enemy to find his own better angels. THAT is Peak Superman.

Superman 2025

And this is why I have zero patience for the trolls and the right-wing extremists and yes even Dean Cain when they start throwing around “Woke Superman” like an epithet when discussing this film. For one thing I am just so fucking sick of hearing the goddamn W-word in any context, but I find it interesting that any time empathy and understanding towards others’ experiences and what they might be going through enters a conversation, that word immediately comes up as a means of attempting to cut off such moves to find common ground at the knees. At the risk of ripping off a few memes that I did not come up with myself: Superman does nothing in this movie that he wasn’t already doing in the comics since Action Comics #1 in 1938. For nearly ninety years, Clark has been defending defenseless people, valuing the sanctity of life above all else, battling those in power who would abuse that power to harm others, and particularly drilling down on self-made billionaires who could have used their hard-earned resources to better the world for everyone and instead choose to horde and harm and destroy in the name of their own narcissism.

And if that last one reminds you of one particular individual in power today, and that realization makes you squirm a little: GOOD.

It’s fucking meant to.

There are certain things happening in the world right now that are just not right. It’s not about political parties or race or religion or nationality or laws. It’s not about who you voted for or what your traditions are. We can argue all we like about whether or not the current president is any good at his job or how to best solve the problems our world faces. But there are certain things that are just plain wrong, regardless of what the law says or the angry shouts of suits from on high who have never and likely will never endure even half of the misery the consequences of their decisions have caused so many. Genocide is wrong. It just is, I don’t care where you’re from or what your religion is. Picking innocent people up off the street, separating them from their children and families for no explicable reason, detaining those people with no due process and left subject to torture and starvation is just wrong. I’m not sure when the hell so many people in this country forgot that, or at the very least numbed themselves to it, and frankly I don’t care. It’s villainy, plain and simple.

If you’re offended by the sight of a guy who has existed for the better part of a century saving lives and protecting the innocent from the draconic actions of the powerful, I would take that as a sign to maybe recalibrate how cynically you may be viewing the world. “Kindness is the New Punk Rock” has become a rallying cry for the empathetic and compassionate for good reason: it just makes sense. And in the spirit of this film and everything Superman actually does represent, I invite those who felt affronted by this film to try looking at it from my perspective, or at least just try a different angle, and see if maybe you might have allowed yourself to hate something that really does no harm to anyone; quite the opposite, in fact. Personally, I’ve never been out to hurt or offend anybody, but I do choose to stand firm against those who do. And I refuse to feel ashamed for caring about other people’s well-being. If there’s anything running through this country right now – the world, even – that deserves shame, it is hatred, cynicism, and turning a blind eye to suffering in the name of egos-in-power.

And that is why this movie is so impactful: it gets why Superman and stories like his matter. They can inspire and cause positive change in the real world when shown in the right lens. And while Clark never deliberately tries to be a messiah to anyone, he certainly would love to see more people help each other simply because they can and they should.

We used to all understand that that is the American Way. It still can be, and God willing, that sense of kindness and compassion still may yet pave the way for a better tomorrow.